Recent Developments

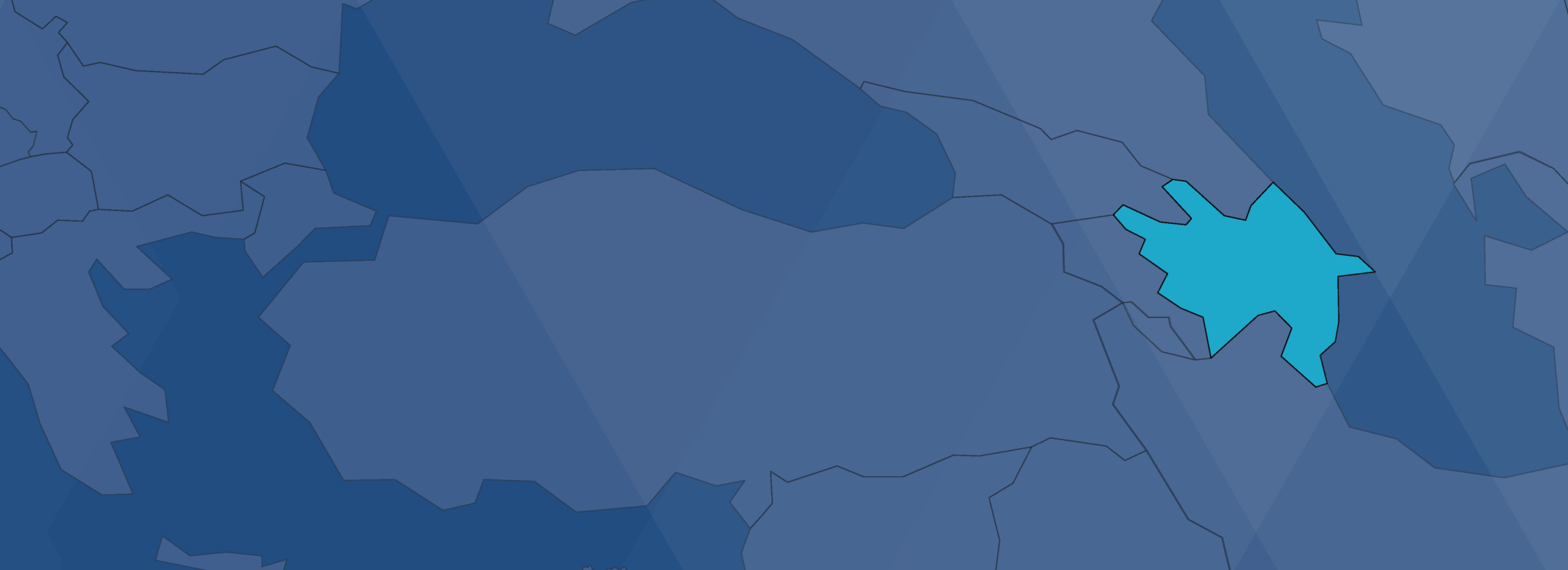

Azerbaijan’s presidential elections in February 2024 resulted in a landslide victory for incumbent President Ilham Aliyev, whose re-election was widely expected following his government’s reclaiming of the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which was formerly controlled by ethnic Armenians. With most of the ballots counted, Aliyev had clearly won the race with 92.1 percent of the votes. Aliyev’s presidency has been characterized by the introduction of increasingly strict laws that restrict political debate as well as arrests of opposition figures and independent journalists, including in the run-up to the presidential election. One and a half years into the new presidential term, journalists and human rights defenders continue to be imprisoned with harsh sentences or held in pre-trial detention. Please see the News Items and Barriers to Expression section below in this report for additional details.

While we aim to maintain information that is as current as possible, we realize that situations can rapidly change. If you are aware of any additional information or inaccuracies on this page, please keep us informed; write to ICNL at ngomonitor@icnl.org.

Introduction

Civil society in Azerbaijan is relatively small, with an estimated 4,766 NGOs registered in the country as of the end of 2021. Complex and burdensome registration procedures present a formidable barrier to the formation of NGOs, and regulatory authorities exercise broad discretion over the approval of organizations, projects, and funding.

Azerbaijan’s legal framework follows a civil law tradition, with laws codified in statutes and regulations rather than developed through judicial precedent. While the constitution guarantees freedoms of expression and assembly, these rights are subject to extensive legal and administrative restrictions in practice. Authorities maintain broad powers to limit public gatherings, control media and online content, and impose sanctions on organizers and participants.

Civic Freedoms at a Glance

| Organizational Forms | Public union, foundation, and union of legal entities |

| Registration Body | Ministry of Justice |

| Approximate Number | 4,766 registered NGOs (as of 2021) |

| Barriers to Formation | (1) Foreigners and stateless persons can be founders of an NGO in Azerbaijan only if they have permanent residence in Azerbaijan. (2) NGO registration must be completed in Baku. (3) Registration applications have often been denied on arbitrary grounds. |

| Barriers to Operations | (1) NGOs must register grant agreements with the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). (2) The MoJ has broad powers to oversee NGOs, including the power to seek their dissolution in court. (3) NGOs operating outside Baku must, in practice, obtain approval from regional executive authorities before holding events. |

| Barriers to Resources | (1) NGOs may receive foreign funding only from foreign donors that have an office in Azerbaijan, have signed an agreement with the MoJ, and have obtained an opinion from the Ministry of Finance on the financial expediency of a grant. (2) NGOs must register all foreign grants, donations, and service contracts with the MoJ. (3) NGOs are prohibited from receiving cash donations, except for up to AZN 200 (USD 120) for NGOs engaged in charity as a primary purpose. (4) NGOs are subject to burdensome requirements relating to AML/CTF compliance. |

| Barriers to Expression | (1) The use of fake usernames, profiles, or accounts to post slander or insults online is punishable by fine or imprisonment. (2) The law prohibits owners of internet resources or users of information-telecommunication networks from allowing false information that results in socially dangerous consequences; the vague wording invites arbitrary application that could infringe upon the freedom of expression. (3) The Media Law provides for increased state control and regulation of media, preventing the media from effectively fulfilling its role as a ‘public watchdog.’ |

| Barriers to Assembly | (1) Organizers must notify authorities at least 5 days in advance. (2) Organizers of an assembly must be citizens and at least 18 years old. (3) Assemblies may be banned near government buildings and designated infrastructure. (4) Assemblies not approved by authorities could result in excessive criminal penalties, including imprisonment. |

Legal Overview

RATIFICATION OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

| Key International Agreements | Ratification* |

|---|---|

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) | 1992 |

| Optional Protocol to ICCPR (ICCPR-OP1) | 2001 |

| Second Optional Protocol to ICCPR, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty (ICCPR-OP2) | 1992 |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) | 1992 |

| Optional Protocol to ICESCR (Op-ICESCR) | No |

| International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) | 1996 |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) | 1995 |

| Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women | 2001 |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) | 1992 |

| International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) | 1998 |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) | 2009 |

| Key Regional Agreements | Ratification |

|---|---|

| European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms | 2001 |

| European Social Charter | 2004 |

* Category includes ratification, accession, or succession to the treaty

CONSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan was adopted on November 12, 1995 (and subsequently amended on August 24, 2002, on March 18, 2009 and on September 26, 2016).

Relevant provisions include:

Article 26. Protection of rights and freedoms of a person and citizen

I. Everyone has the right to protect his/her rights and freedoms using means and methods not prohibited by law.

II. The state guarantees protection of rights and freedoms of all people.

Article 49. Freedom of assembly

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of assembly with others.

2. Everyone has the right, having notified respective governmental bodies in advance, peacefully and without arms, to meet with other people, organize meetings, demonstrations, processions, place pickets without violating public rule and public moral.

Article 58. Right to associate

I. Everyone is free to associate with other people.

II. Everyone has the right to establish any union, including a political party, trade union and other public organization or to enter existing organizations. Unrestricted activity of all unions is ensured.

III. Nobody may be forced to join any union or remain its member.

IV. Activity of unions which intend forcible overthrow of legal state power on the whole territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan or in any part thereof and other objectives which are considered a crime, or the usage of criminal methods are prohibited. Activity of unions which violates the Constitution and laws might be stopped by decision of law court.

Article 60. Guarantee of rights and freedoms by court of law

I. Everyone is guaranteed the protection of his/her rights and liberties in the administrative manner and in court.

II. Everyone has the right to an unbiased approach to their work and consideration of the case within a reasonable time in the administrative proceedings and litigation.

III. Everyone has the right to being heard in administrative proceedings and litigation.

IV. Everyone may appeal to court in the administrative manner against the actions and inaction of public authorities, political parties, legal entities, municipalities and their officials.

Article 151. Legal value of international acts

Whenever there is disagreement between normative-legal acts in legislative system of the Republic of Azerbaijan (except Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan and acts accepted by way of referendum) and international agreements wherein the Republic of Azerbaijan is one of the parties, provisions of international agreements shall dominate.

NATIONAL LAWS, POLICIES, AND REGULATIONS

Relevant national-level laws and regulations affecting civil society include:

- The Constitution of Republic of Azerbaijan, 12 November 1995 (subsequently amended on 24 August 2002 and on 18 March 2009);

- The Civil Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan (28 December 1999, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on Non-Governmental Organizations (Public Associations and Foundations) (13 June 2000, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on the State Registration and State Register of Legal Entities (12 December 2003, with subsequent amendments);

- The Concept of State Support to Non-Governmental Organizations of the Republic of Azerbaijan (27 July 2007);

- Regulations of the Agency of State Support to Non-Governmental Organizations under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan (19 April 2021);

- The Tax Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan (11 July 2000, with subsequent amendments);

Code on Administrative Offences of the Republic of Azerbaijan (11 July 2000, with subsequent amendments); - Labour Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan (1 February 1999, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on Grants (April 1998, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on Obtaining Information (30 September 2005);

- The Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Azerbaijan #376 on International Humanitarian Organizations and their Representatives Offices in the Republic of Azerbaijan (2 November 1994, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on State Fees (4 December 2001, with subsequent amendments);

- The Law on Voluntary Activity (9 June 2009);

- Rules on Conducting Negotiations for Preparation and Signing of an Agreement for the State Registration of Branches or Representative Offices of International Non-governmental Organizations in the Republic of Azerbaijan (16 March 2011);

- Law on Public Participation (adopted on 22 November 2013; will enter into force as of 1 June 2014); and

- The Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Azerbaijan # 216 on approval of Rule on Registration of Grant Agreements/Contracts (Decisions/Orders) (5 June 2015).

- Rules on Studying the Activities of Non-Governmental Organizations, Branches or Representative Offices of Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations (December 28 2015).

- Rules on obtaining the right to provide grants in the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan by foreign donors (22 October 2015).

- Rules on registration of service contracts on provision of services or implementation of work by NGOs, as well as by branches or representations of foreign NGOs from foreign sources (20 November 2015).

- Rules on submission of information about amount of donation received by NGOs as well as by branches or representations of NGOs of foreign states and about the donor (13 November 2015).

PENDING REGULATORY INITIATIVES

If you are aware of other pending legislative initiatives not included here, please contact ngomonitor@icnl.org.

Legal Analysis

ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS

Azerbaijani legislation refers to both “non-governmental organizations” (NGOs) and “non-commercial organizations” (NCOs). Under the Civil Code, a non-commercial legal entity is one whose main purpose is not generating profit and which does not distribute any profit among its members. NCOs include public unions, foundations, and unions of legal entities. The Law on Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO Law) sets out the legal framework for public unions and foundations.

The main types of NCOs are:

- Public union – A voluntary, self-governed NGO established by several physical and/or legal persons united on the basis of common interests. Its purposes, as defined in its founding documents, must not be aimed primarily at generating profit, and any profit earned may not be distributed among its members (Article 2.1, NGO Law).

- Foundation – A non-membership NGO established by one or more physical and/or legal persons through the contribution of property, with the aim of carrying out social, charitable, cultural, educational, or other activities serving the public interest (Article 2.2, NGO Law).

- Union of Legal Entities – An association of legal entities, which may be founded by commercial organizations, NCOs, or both, to coordinate activities and represent and protect their interests—including property interests—before state and other bodies, international organizations, and other entities (Articles 117.1 and 117.2, Civil Code).

The vast majority of registered NGOs in Azerbaijan are public unions.

PUBLIC BENEFIT STATUS

The Tax Code defines a charitable organization as a “non-commercial organization which conducts charitable activities” (Article 13.2.36). Charitable activity is described as providing direct assistance—monetary or otherwise—without compensation to individuals in need, or to organizations that directly provide such assistance. This can also include scientific, educational, or other activities carried out in the public interest, unless otherwise specified in the Code (Article 13.2.35).

Charitable organizations are exempt from profit tax, except for income derived from entrepreneurial activities (Article 106.1.1). However, no law specifies how an organization can obtain or demonstrate “charitable organization” status, making it practically impossible to benefit from the exemption in practice. It is also unclear whether an organization must exclusively engage in charitable activities to qualify, or whether an NCO conducting both charitable and non-charitable activities could still be eligible. (See M. Guluzade and N. Bourjaily, Charity in Azerbaijan: Prospects for Developing Legislation and Practice.)

“International humanitarian organizations and other branches of foreign entities engaged in charitable activities” must secure approval from the Cabinet of Ministers before registering with the Ministry of Justice. Domestic NGOs, by contrast, can register directly with the Ministry of Justice without Cabinet approval.

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

Despite the existence of some positive legislative—including the Law on Public Participation—that allows for the participation of NGOs in the decision-making process, the role of civil society in the development of laws is limited in practice.

BARRIERS TO FORMATION

Azerbaijani law permits the establishment and operation of informal associations (Article 15 of NGO Law), and in practice, unregistered (unincorporated) domestic NGOs are not restricted. However, since 2013, unregistered foreign NGOs have been prohibited from operating in the country and are subject to financial penalties.

NGO registration must be completed in Baku. Founders may be legal persons (excluding state bodies and local self-governments) or physical persons aged 18 or older. Individuals as young as 16 may found youth public unions. Amendments to the Law on Youth Policy in 2019 require that founders and members of youth organizations be under the age of 35. Foreigners and stateless persons may serve as NGO founders—or as legal representatives of foreign NGOs—if they have permanent residence in Azerbaijan. There are no legal restrictions preventing foreigners or stateless persons from becoming NGO members or assistants.

Despite these provisions, both domestic and international NGOs face significant practical challenges in obtaining registration. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has ruled against the Government of Azerbaijan in at least 32 cases involving the denial of NGO registration, finding violations of the right to freedom of association. In May 2021, the ECtHR determined that Azerbaijan had infringed the rights of 25 CSOs.

BARRIERS TO OPERATIONS

Azerbaijani law imposes numerous restrictions on the operational activities of NGOs:

- Grant Registration – NGOs may not carry out banking or other transactions involving grant funds unless the grant agreement is registered with the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). Violations can result in fines of AZN 5,000-8,000 (USD 2,940-4,700 as of August 2025).

- Financial Penalties – The law prescribes significant fines for violations of NGO legislation, including failure to align founding documents with domestic law (applicable to both local and foreign NGOs), implementing activities based on unregistered amendments to founding documents, failure to register grant agreements, failure to maintain a membership registry, or not concluding contracts with volunteers. Penalties are often applied at the discretion of the authorities. For example, failure to register a grant agreement may result in fines ranging from AZN 1,000-2,500 (USD 588-1,470), a broad range with no clear criteria for determining the amount.

- Ministry of Justice Oversight – The MoJ has broad supervisory powers, including the authority to issue warning letters. If an NGO receives more than two warnings within a year, the MoJ may seek its involuntary dissolution through the courts.

- Regional Approvals – Although not required by law, NGOs operating outside Baku are expected to obtain approval from regional executive authorities before holding events.

- Political Activity Restrictions – Under Article 2.4 of the NGO Law, NGOs may not participate in presidential, parliamentary, or municipal elections, or provide financial or material assistance to political parties.

2014 Legislative Amendments

With changes to NGO legislation introduced in 2014:

- Individuals receiving grants must register them with the MoJ in the same way as organizations;

- Branches and representative offices of foreign NGOs must provide the names, citizenship, and residence of their chief and deputy chief of party to the MoJ;

- Agreements between foreign NGOs and the MOJ signed as part of the registration process must have an expiration date;

- Courts may suspend an NGO’s activities based on a lawsuit filed by its members; and

- All NGOs, including branches and representations of foreign NGOs, must have formal contracts for any goods, property, or rights received in the form of assistance.

Rules on Studying NGO Activities

In December 2015, the MoJ adopted the Rules on Studying the Activities of Non-Governmental Organizations, Branches or Representative Offices of Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations, which were published in February 2016. The Rules grant the MoJ broad authority to inspect NGOs for compliance with their charters and national legislation, covering issues such as management meetings, membership registries, financial reporting, grant and accounting compliance, and adherence to other relevant legal acts. The MoJ may also involve other state bodies or NGOs in these inspections, which can last up to 60 days. These rules apply to both local NGOs and registered offices of foreign NGOs.

Inspections may include document requests via the Personal e-Window system, on-site visits, hard copy submissions, or requiring NGO staff to appear at the MoJ. NGOs must provide inspectors with office space, a copy machine, a computer, and other facilities, while the Rules place few restrictions on the number or conduct of inspectors. Although the Rules state that inspections should not impede NGO operations, there are no enforcement mechanisms to guarantee this safeguard.

Failure to comply with the Rules—such as failure to respond to inquiries or submit required information or giving false information—can result in sanctions on the NGO in accordance with the Code on Administrative Offenses.

BARRIERS TO RESOURCES

Foreign Funding

Since 2015, the government has imposed restrictive requirements on donor registration and registering foreign grants, service contracts, and donations, seriously limiting NGOs’ access to foreign funding. These rules have left hundreds of NGOs without substantial resources and prompted many skilled professionals to leave the sector. The funding restrictions reflect the government’s hostile attitude toward NGOs, which are often referred to as “anti-government” or “foreign agents.”

NGOs may receive foreign funding only from foreign donors that have an office in Azerbaijan, have signed an agreement with the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), and have obtained an opinion from the Ministry of Finance (MoF) on the financial-economic expediency of a grant. NGOs must register all foreign grants, donations, and service contracts with the MoJ. For grants, NGOs must submit an application, the original grant agreement, and other supporting documents to the MoJ within 30 days of the grant’s signature. Failure to do so results in fines of up to AZN 7,000 (USD 4,100 as of August 2025) in accordance with Article 432 of the Administrative Code.

Receiving aid without a grant contract (if not a donation) can lead to the confiscation of funds or assets, fines of AZN 8,000-15,000 (USD 4,700-8,800) for NGOs, and fines of AZN 2,500-5,000 AZN ($1,470-2,940) for NGO managers. These penalties apply equally to domestic NGOs and representative and branch offices of foreign NGOs.

Foreign NGOs may receive donations from foreign donors only if they have an MoJ agreement, and report donation amounts and donor details to both the MoJ and the MoF before carrying out any related transactions.

Economic Activities

NGOs may engage in economic activities, but profits are taxed in the same way as those of commercial organizations.

Grants and Donations

Amendments to the Law on NGOs in March 2013 defined donations as funds or materials given to an NGO “without a condition to achieve any purpose.” Both donors and recipients are prohibited from promising or receiving anything in return.

NGOs must register all donations with the MoJ. February 2014 changes to NGO legislation extended grant-registration requirements to individuals.

NGOs are generally prohibited from receiving cash donations, except for up to AZN 200 (USD 120) for NGOs whose charters list charity as a primary purpose.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

In March 2020, the Cabinet of Ministers issued Decision #88, which introduced a mechanism for CSR. The decision, which was adopted without consulting NGOs and other stakeholders, limits the recipients of business funds to NGOs active in the cultural field.

Public Funding

State funding mechanisms provide small grants to NGOs, generally not exceeding EUR 3,000-5,000 (USD 1,760-2,940). All government bodies wanting to issue NGO grants must coordinate with the Agency for State Support to NGOs, which replaced the NGO Support Council in April 2021.

Anti-Money Laundering/Countering Terrorism Financing (AML/CTF) Regulations

On January 31, 2023, amendments to the Law on Combating the Legalization of Property Obtained through Crime and the Financing of Terrorism and the Code of Administrative Offenses introduced new compliance obligations for NGOs. Organizations must adopt internal procedures to minimize AML/CTF risks, submit detailed annual reports on grants and donations and their use to the supervisory body by April 1, and conduct annual risk assessments. Noncompliance may result in the suspension or termination of licenses, registrations, permits, and certificates. Under Article 598.8 of the Administrative Code, NGOs face fines of AZN 10,000–20,000 (USD 5,880–11,760), and their officials face fines of AZN 2,000–4,000 (USD 1,180–2,350) for failing to implement required AML/CTF measures.

BARRIERS TO EXPRESSION

Article 47 of the Constitution of Azerbaijan guarantees the freedom of thought and speech. In practice, however, the exercise of this right faces numerous limitations.

Under Article 148-1 of the Criminal Code, using fake user names, profiles, or accounts to post slander or insults online is punishable by a fine of AZN 1,000-2,000 (USD 590-1,180 as of August 2025), community service for 360-480 hours, corrective labor for up to two years, or imprisonment for up to one year.

On March 17, 2020, amendments to the Law on Information, Informatization, and Protection of Information were passed that prohibit owners of internet resources or users of information-telecommunication networks from allowing false information that threatens human life or health, causes significant property damage, violates public safety, disrupts critical infrastructure, or results in other socially dangerous consequences. These provisions are broadly worded and could be used to hinder freedom of expression on social media.

On December 30, 2021, Parliament adopted a new Media Law that provides for increased state control and regulation of media. On June 20, 2022, the Venice Commission and the Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law of the Council of Europe issued a joint opinion noting that “many provisions are not in line with European standards on freedom of expression and media freedom and do not allow the media to effectively exercise its role as a ‘public watchdog.’”

In a potentially positive development, a May 2022 amendment to the Law on State Duty significantly lowered the licensing fee for nationwide terrestrial television broadcasters from AZN 50,000 (USD 29,400) to AZN 5,000 (USD 2,940), which could enable the establishment of new broadcasters.

In April 2023, amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses expanded the responsibilities of NGOs conducting media-related activities and introduce harsher penalties for violations. Under Article 281, fines range from AZN 200-10,000 (USD 115 – 5,900), which can be burdensome for NGOs. Article 388 imposes fines of AZN 200-3,000 (USD 115-1,760) on journalists and editors for disseminating prohibited information or disclosing the source of information when not permitted by law.

BARRIERS TO ASSEMBLY

Notification

Organizers of an assembly, defined as a “gathering of several people,” must notify authorities at least five days in advance. The regulatory authority is required to respond within three days. If the notification is denied, organizers may appeal to an administrative or judicial body within three days.

Restrictions on Organizers

Organizers must participate in the assembly, be at least 18 years old, and wear distinctive signs during the event. Foreign citizens, stateless persons, and minors are prohibited from serving as organizers.

Time, Place, and Manner Restrictions

Assemblies may be banned within a 200-meter radius of the Milli Majlis, the Presidential Palace, high-level government buildings in the Nakchivan Autonomous Republic, the Supreme and Constitutional Courts, highways, tunnels, bridges, electrical networks exceeding 1,000 volts, and venues used by local government officials for public events. A 150-meter exclusion zone applies to military facilities, prisons, and hospitals.

Local authorities may designate “special places” for assemblies, adjust the time of an assembly if deemed “necessary and proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued,” and ban assemblies on the eve of days of “national importance.” Assemblies may also be restricted during emergencies, on election days, or when they have “political content.” The use of amplifiers above 10 watts is banned. Counter-demonstrations are generally allowed, though authorities can recommend changes to their time and location.

Criminal Penalties and Enforcement

Participants and organizers can be fined for holding an assembly without permission, even if no harm or disturbance occurs. Assemblies not approved by authorities and that involve a “substantial violation of the rights and legitimate interests of citizens” carry penalties under Article 169 of the Criminal Code. These include fines of AZN 5,000-8,000 (USD 2,940-4,700 as of August 2025), correctional labor for up to two years, or imprisonment for up to two years. Police use of force against organizers and participants in assemblies is not uncommon.

Additional Resources

GLOBAL INDEX RANKINGS

| Ranking Body | Rank | Ranking Scale (best – worst possible) |

|---|---|---|

| UN Human Development Index | 81 (2023) | 1 – 193 |

| Transparency International | 154 (2024) | 1 – 180 |

| Fund for Peace Fragile States Index | 72 (2024) | 179– 1 |

| Freedom House: Freedom in the World | Status: Not Free Political Rights: 0 Civil Liberties: 7 (2025) | Free/Partly Free/Not Free 40 – 0 60 – 0 |

REPORTS

| UN Universal Periodic Review Reports | Azerbaijan UPR page |

| International Azerbaijan Academic Research Congress | Development of Civil Society Organizations in Azerbaijan: Relations with Civic and Public Spaces (2022) |

| Reports of UN Special Rapporteurs | Azerbaijan |

| U.S. State Department | 2024 Human Rights Reports: Azerbaijan |

| Fragile States Index Reports | Fragile States Index |

| Amnesty International | Azerbaijan |

| Human Rights Watch | World Report 2025: Azerbaijan |

| European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL) | CSO METER: A compass to conducive environment and CSO empowerment (2023) |

| International Center for Not-for-Profit Law Online Library | Azerbaijan |

NEWS

Authorities should release imprisoned human rights defenders, journalists and civil society activists (April 2025)

In 2018 the European Court of Human Rights (the Court) held that Mr Mammadli’s arrest in 2013 on similar charges as those he is facing today violated the European Convention on Human Rights because there was no reasonable suspicion of his having committed a criminal offence and the actual purpose of his arrest was to silence and punish him. Today, most of the human rights defenders, journalists and civil society activists who are imprisoned are in pre-trial detention like him, but several have already been convicted to harsh sentences. This includes civil society activist Bakhtiyar Hajiyev who was sentenced to 10 years on January 13, 2025; Aziz Orujov, the director of Kanal 13, an independent media, who was handed a two-year prison sentence on February 26, 2025; and opposition activist and former journalist, Tofig Yagublu, who was jailed for nine years on March 10, 2025.

Azerbaijan’s escalating crackdown on critics and civil society (October 2024)

Azerbaijan has had a poor human rights record for many years, with the government regularly targeting those who play important watchdog roles in society, including human rights defenders, journalists, and independent civic activists. The government’s vicious crackdown on critics and dissenting voices intensified over the last two years. Among the methods the government uses to target these individuals are arrests and prosecutions on politically motivated, bogus criminal charges, as well as the arbitrary enforcement of highly restrictive laws regulating non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This system effectively excludes independent activists and media from lawful ways of carrying out their work, thereby pushing them to the margins of the law and heightening their vulnerability to retaliatory criminal prosecution.

Repression escalating ahead of presidential elections (February 2024)

Ahead of Azerbaijan’s early presidential election on February 7, Amnesty International draws urgent attention to the authorities’ latest crackdown on the right to freedom of expression, including the targeting of critical voices by Ilham Aliyev, the incumbent head of state. Since November 2023, the Azerbaijani authorities have stepped up their repression of peaceful dissent, resulting in the arrests of more than 13 individuals, including journalists, political opponents, and a human rights defender. Of these individuals, at least 11 remain in arbitrary detention on spurious charges. Many more dissenting voices, including journalists, have fled the country fearing prosecution.

Azerbaijani Authorities Close Criminal Case against NGOs (June 2023)

The investigative department of the General Prosecutor’s Office of Azerbaijan closed the criminal case against several NGOs, which was started back in 2014. The heads of the organizations were recently invited to the investigative department and were informed that the case had been closed.

ARCHIVED NEWS

HRW Says Azerbaijan Abuses COVID-19 Restrictions to Crack Down on Critics (April 2020)

National Action Plan on Promotion of Open Government Approved (February 2020)

Presentation of CSO Meter (December 2019) (Azeri)

New public funding for local NGOs (November 2019) (Azeri)

NGO Support Council Presents 20 new e-services for CSOs (October 2019) (Azeri)

New Accounting Standards approved for NGOs (January 2019) (Azeri)

Restriction on establishing NGOs in armed forces (June 2018)

Another ground for suspension of NGOs’ activity (May 2018)

U.S. committed to cooperation with Azerbaijan for sake of development (February 2018)

Public Legal Entities Can Receive Grants (July 2017)

Hotline established under NGO Council (May 2017)

Azerbaijan’s human rights record reviewed by the UN Human Rights Committee (October 2016)

Council of Europe’s Venice Commission issues Preliminary Opinion on Referendum (September 2016)

Welcoming the Release of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan (March 2016)

European Parliament adopts a Resolution on Azerbaijan (September 2015)

Khadija Ismayıl and Leyla Yunus are listed for US State Department’s campaign (September 2015)

Baku closes OSCE Office (June 2015)

ECHR announces a new decision against Azerbaijan (May 2015)

Azerbaijan’s status in EITI downgrades to candidate (April 2015)

European Court: Azerbaijan violated NGO’s freedom of association (November 2014)

NGO Bank Accounts Frozen (August 2014)

Azerbaijani Activist Faces Imminent Arrest for Creating Peacebuilding Website (December 2013)

Government arrests leading members of civil society ahead of high-level diplomatic visit (December 2013)

Penalty for unauthorized assemblies increased (June 2013)

Rights to freedom of expression eroded even further (May 2013)

Mood darkens in Baku amid crackdown on civil society (January 2013)

PACE rapporteurs express concerns about freedom of assembly and expression in Azerbaijan (November 2012)

Azerbaijani MP: NGOs’ state funding should be increased (November 2012)

Can Facebook become substitute for live opposition protests? (November 2012)

Ahead of Presidential elections in 2013 Azerbaijani government proposes to toughen legislation on public protests (November 2012)

New Azerbaijani law on unsanctioned public gatherings (November 2012)

OSCE appreciates Azerbaijani authorities’ readiness for dialogue on freedom of speech (November 2012)

Azerbaijani parliament adopts tougher legislation on unauthorized rallies (October 2012)

Joint submission outlines concerns related the CSO environment in Azerbaijan for UPR (October 2012)

Cabinet of Ministers adopts rules that hinder access to information (July 2012)

President promulgates changes to the law “on commercial secrets” (July 2012)

“Non-provision” of statistical reports means new penalties applicable to NGOs (June 2012)

Crackdown in Azerbaijan after the 2012 Eurovision contest (July 2012)

Top official: Most issues raised by NGOs fully coincide with Azerbaijani government’s policy (July 2012)

Azerbaijani civil society condemns proposed amendments to draft laws on Freedom of Information (June 2012)

Increased support needed for civil society in Azerbaijan after Eurovision contest (May 2012)

One-stop shop for registration of NGOs and Civil Society Concept suggested in Azerbaijan (May 2012)

European Parliament resolution on Azerbaijan mentions pressure on NGOs (May 2012)

Venice Commission expresses views on Azerbaijan’s NGO law (April 2012)

Law on Social Service set to enter into force in June 2012 (March 2012)