Recent Developments

While we aim to maintain information that is as current as possible, we realize that situations can rapidly change. If you are aware of any additional information or inaccuracies on this page, please keep us informed; write to ICNL at ngomonitor@icnl.org.

Introduction

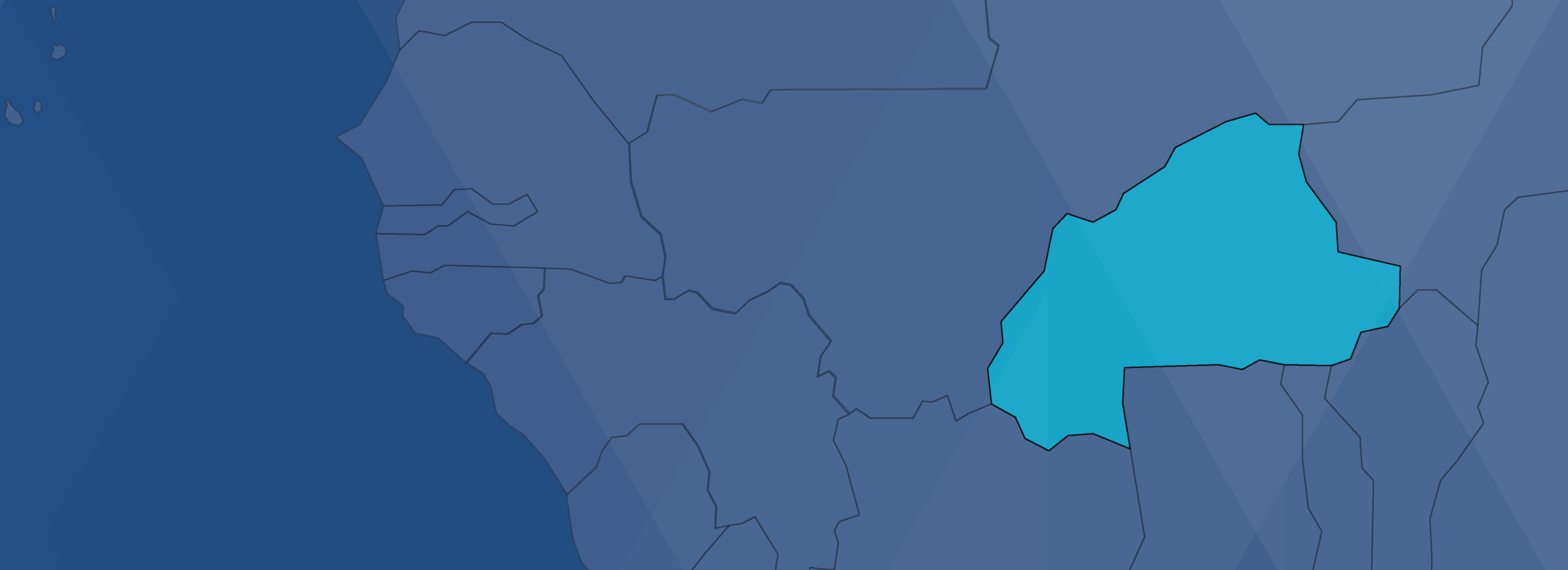

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa. Formerly known as the Republic of Upper Volta, the country was renamed “Burkina Faso” – meaning “Land of Incorruptible People” – on August 4, 1984. Previously, the country had been a French colony from 1919 until gaining independence on August 5, 1960. After 1960, independent institutions in Upper Volta were not yet fully established, and colonial-era French laws stayed in place. A French law governing freedom of association remained in force from 1958 until 1992.

A new Constitution was adopted on June 2, 1991, and on December 15, 1992, the National Assembly enacted Law 10/92, which instituted a legal regime that encouraged the growth in the number of associations. Supported by Law 10/92, civil society played an increasingly large role on issues of public importance, including social, economic, and humanitarian services for the poor, and citizen oversight of human rights and governance. In addition, civil society has often played an important political role, such as during the struggle against constitutional amendments in 2014, which led to a popular uprising in October 2014 and a political transition in 2015.

Law 10/92 was replaced in 2015 by Law 064-2015 CNT, which addressed a number of flaws in the prior legal framework. Under Law 064-2015/CNT, civil society organizations (CSOs) are able to form freely and do not need advance government approval. They may pursue any legal purpose, defined in the bylaws of the organization, along with internal decision-making bodies and management rules. They can seek and secure registration by submitting declarations of their existence along with draft bylaws, internal regulations, and other information to the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization, and Security (MATDS). Equally noteworthy is the fact that the intervention of civil society actors, and particularly human rights defenders (HRD), is guaranteed and protected by Law 039-2017 on the protection of HRD in Burkina Faso. Such interventions can also be carried out by foundations, as per Law N°008-2017AN on the legal regime applicable to Foundations in Burkina Faso.

Civic Freedoms at a Glance

| Organizational Forms | Associations, NGOs, and Trade Unions |

| Registration Body | Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization, and Security (MATDS) |

| Approximate Number | While the number of associations is uncertain, there are reportedly 17,000 NGOs. |

| Barriers to Formation | No significant barriers to entry. |

| Barriers to Operations | The law prohibits vaguely defined acts, including those contrary to “proper mores” or “the dignity of human persons.” |

| Barriers to Resources | No legal barriers impeding either domestic or international funding, but there are cases of the government pressuring organizations to not receive funding through international cooperation. |

| Barriers to Expression | The law imposes vague conditions on “professional” online media services by requiring them to avoid content that can shock or undermine human dignity or decency; and prohibits the dissemination of “fake news” without defining the term. The Penal Code (2018) also imposes some barriers to speech, and following its amendment in 2019 it has been intended to facilitate the fight against terrorism by strengthening the control of the content of information primarily in connection with national security. Some provisions of the Code (arts. 312-11, 13, 14, 15, 16) have also been criticized for restricting freedom of the press and freedom of expressing in general. |

| Barriers to Assembly | Prior authorization required, and authorities have broad powers to forbid or dispel an assembly. Organizers of assembly where violence or property damage occurs are subject to criminal sanctions, including imprisonment. |

Legal Overview

RATIFICATION OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

| Key International Agreements | Ratification* |

|---|---|

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) | 1999 |

| Optional Protocol to ICCPR (ICCPR-OP1) | 1999 |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) | 1968 |

| Optional Protocol to ICESCR (Op-ICESCR) | No |

| International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) | 1974 |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) | 1987 |

| Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women | 2005 |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) | 1990 |

| International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) | 2003 |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) | 2009 |

| Key Regional Agreements | Ratification |

|---|---|

| African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights | 1984 |

* Category includes ratification, accession, or succession to the treaty

CONSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

Adopted by referendum in 1991, the Constitution enshrines respect for political pluralism, the separation of powers, and civil and political liberties. It articulates rights that are generally consistent with international norms, as reflected in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1981 African Charter on Human and People’s Rights.

Specifically, the Constitution provides for the freedom of assembly, procession, and demonstration (Article 7); the freedom of opinion, the right to information, and freedom of expression (Article 8); and the right of citizen participation in governance without exception (Article 12). The freedom of association is enshrined in Article 21, which states that: “Freedom of association is guaranteed. All persons have the right to form associations and to participate freely in activities of existing associations. Associations must act within the confines of existing laws and regulations.”

While the Constitution generally recognizes civic freedoms, its provisions include legal compliance clauses, such as “within the confines of existing laws and regulations.” These clauses may open the door to restrictions, as constitutional rights become subject to laws and regulations passed by the government.

NATIONAL LAWS, POLICIES, AND REGULATIONS

The current Transition Charter (adopted October 14, 2022) contains a conflict of laws clause, which may open doors to laws or regulations that affect the enjoyment of constitutional rights by the civil society. Its Article 24 states, “In case of conflict between the Transition Charter and the Constitution of June 2, 1991, the provisions of this Charter shall apply”. In addition, several laws and regulations (e.g., decrees) may directly or indirectly affect civil society:

- Law 064-2015/CNT of October 20, 2015, concerning freedom of association (replacing Law 10/92 of December 15, 1992)

- Law 22/97 concerning freedom of manifestations and public demonstrations

- Law 051/2015 concerning access to public information

- Law 056/1993 concerning information (the Information Code)

- Law 001-2021/AN protecting personal data

- Law 057/2015 concerning the legal status of printed media

- Law 058/2015 concerning the legal status of online press

- Law 059/2015 concerning the legal status of radio broadcasting

- Law 039/2017/AN concerning the protection of human rights defenders in Burkina Faso

- Law N°008-2017/AN on the legal regime applicable to Foundations in Burkina Faso

- Decree N°2008-154/PRES/PM/MEF of April 02, 2008 on the organization of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, which establishes the General Directorate for Cooperation (DG-COOP), with a Directorate for NGO Monitoring (DSONG)

- Decree concerning PNDES (Plan National de Développement Economique et Social)*

- Law 055-2004/AN concerning the General Territorial Collectivities Code

- Decree No. 2023-0475/PRES-TRANS/PM/MDAC/MJDHRI concerning the general mobilization and warning (mobilisation générale et mise en garde)

* Numbers are not available for these decrees.

PENDING REGULATORY INITIATIVES

There are currently no pending initiatives to amend the legal framework affecting civil society or the freedoms of association, assembly, and expression. These initiatives are also contained in the Action Plan for Stabilization and Development (Plan d’actions de stabilization et de développement, PA-SD), which was adopted by the transitional government.

Legal Analysis

ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS

Article 2 of Law 064/2015/CNT governs three organizational types, including (1) associations, (2) non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and (3) trade unions.

Excluded from the application of the law are associations pursuing purely political or commercial goals or objectives. This clause leads to uncertainties due to the imprecise notion of “purely political or commercial.”

Under Article 3 of Law 064, an association is defined as any group of natural or legal persons, whether national or foreign, with a permanent, non-profit vocation and the aim of achieving common objectives, particularly in the cultural, sporting, social, spiritual, religious, scientific, professional, or socio-economic realms. A foreign association is any association whose head office is located outside Burkina Faso. An association of recognized public utility (ARUP) is any association or association of associations whose activities pursue an aim of general interest, particularly in the areas of economic, social, and cultural development in a specified region.

A non-governmental organization (NGO) is defined as any declared national association or authorized foreign association engaged in the field of economic, social, or cultural development of the country or a specified region. To become an NGO, a national association must obtain approval through an agreement with the Ministry of the Economy and Finance, and a foreign association must conclude “une convention d’établissement” (framework agreement) with the Ministry of the Economy.

A trade union is defined as any organization or group of workers that seeks to promote and defend the moral, material, and professional interests of its members, or any free association of workers or employees exercising the same occupation, similar trades, or related professions contributing to the establishment of specific products.

The legal status and the financial regimes governing foundations derive from common law under Law 008 of 2017.

There used to be much uncertainty about the precise number of CSOs in Burkina Faso, in part due to the multiple locations where CSOs were registered. Registration occurred both centrally (at the Ministry) and locally (at the regional, provincial, and commune levels). No centralized registration system existed. Since 2010, the Territorial Administration and Decentralization Ministry (MATD) has undertaken efforts to better record registrations. Currently, there are approximately 17,000 NGOs in Burkina Faso.

PUBLIC BENEFIT STATUS

There is no comprehensive legislation defining the tax treatment of CSOs in Burkina Faso. Tax exemptions are available for NGOs, but not for associations or trade unions. These exemptions are addressed in the “Convention d’établissement” (or Framework Agreement) that must be endorsed by the Council of Ministers (Articles 32 and 33 of Law 064). This agreement is akin to a memorandum of understanding that provides the NGO with official recognition as a government partner and confers benefits, including tax exemptions.

The preferential tax treatment for NGOs likely springs from the involvement of NGOs in providing humanitarian services during the droughts of the 1970s, at which time, tax exemptions were extended to them to facilitate their work.

In 2016, the government attempted to adopt a decree amending the tax treatment of NGOs. Had it been adopted, the decree would have eliminated tax exemptions altogether and would have subjected foreign funds received by NGOs to taxation. In response, however, the NGO Permanent Secretary (SPONG), which is an independent, umbrella NGO, mobilized push-back and prevented the adoption of the decree.

Associations of Recognized Public Utility (ARUP) do not yet benefit from tax exemptions but receive subsidies from the state, depending on available state funds. They are required to submit annual reports with financial statements to the Territorial Administration and Decentralization Ministry (MATD), the Ministry of Economy and Finance, and their line ministries. Failure to submit the reports can result in the suspension of funding, although this is not known to have happened. NGOs are similarly supposed to submit annuals reports to the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Corporations and individuals may receive deductions for donations to all types of CSOs.

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

The Constitution of Burkina Faso (June 2, 1991) guarantees to every Burkinabe citizen the right to participate in public governance. The Constitution provides that the right can be exercised individually (article 12) or collectively through political parties (article 13) or not-for-profit organizations and even trade unions (article 21), as well as at the national and decentralized levels of public governance (article 145 on territorial collectivities) and in all sectors of public governance (politics, environment, security, agrarian and land management, etc.). Procedures and mechanisms for civic participation are set forth under various laws and regulations, including, most notably, the consultation frameworks (‘Cadres de concertation’) that have been put in place at the national, regional, provincial and communal levels to facilitate public participation in matters relating to development projects. Equally noteworthy are the mechanisms relating to the “Proximity Police (Community Police)” through which communities participate in the security sector, particularly at the local level.

Similarly, in order to regulate public participation and civic involvement in the fight against terrorism, the transition government adopted a decree concerning the “general mobilization and warning” (mobilisation générale et mise en garde). This regulatory instrument, on the one hand, encourages citizens’ initiatives in support of the Defense and Security Forces and, on the other hand, provides that some rights and freedoms will be limited in certain circumstances. The decree will be implemented for 12 months from April 2023.

Other laws protecting public participation include:

- Law No. 032-2001/AN of November 2001 on the Charter of Political parties

- Law No. 032-2003 of May 2003 on Interior Security

- Law No. 055-2004/AN of December 2004 on Territorial Collectivities (‘General Code of Territorial Collectivities’)

- Law No. 012-2010/AN of April 2010 on the protection and promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities

- Law No. 034-2012/AN of July 2012 on Agrarian and Land Reorganization

- Law No. 006-2013/AN of April 2013 on the Environment (‘Environmental Code’)

- Law No. 064-2015/CNT of October 2015 on Freedom of Association

- Law n°061-2015/CNT of September 2015 on the prevention, repression and reparation of violence against women and girls, and care for victims

- Law n°024-2016/AN of October 2016 on the protection and promotion of the rights of older persons

- Law No. 003-2020/AN of January 2020 setting the Quota and modalities of positioning of candidates for legislative and municipal elections (‘Law on Gender Quota’)

- Law No. 003-2023/ALT of March 2023 on Monitoring and development committees (Comités de veille et de dévéloppement, COVED)

Decrees related to organizing public participation include:

- Decree No. 2009-837/PRES/PM/MEF/MAHRH/MATD of December 2009 on the creation, attributions, composition and organization of the National Consultation Framework of Decentralized Rural Development Partners (CNC-PDR)

- Decree No. 2009-838/PRES/PM/MEF/MATD of December 2009 on the creation, attributions, composition and functioning of Consultation frameworks for decentralized rural development (at regional, provincial and communal levels)

- Decree No. 2015-1187/PRES/TRANS/PM/MERH/MATD/MME/MARHASA/MRAMI on the conditions and procedures for conducting and validating the Strategic environmental assessment, and the Environmental and social impact study and notification

- Decree No. 2016-1052/PRES/PM/MATDSI/MJDHPC/MINEFID/MEEVCC of December 2016 defining the modalities of participation of the populations in the implementation of Proximity Police

- Decree No. 2023-0475/PRES-TRANS/PM/MDAC/MJDHRI concerning the general mobilization and warning (mobilisation générale et mise en garde)

Public Awareness

Public awareness about mechanisms for public participation is still limited in Burkina Faso, despite the fact that the government has been taking steps to provide information about such mechanisms to the public.

Under the Burkinabe legal system, a law enters into force 21 clear days after its promulgation and publication in the Journal Officiel (or the ‘Gazette’). This period is reduced to eight days in case of an emergency declared by the National Assembly (Article 48 of the Constitution). However, the Journal Officiel remains inaccessible to most of the population, and particularly those with little or no knowledge of the country’s official language (French) or who are living in rural areas. To deal with this situation, the government has attempted to publicize mechanisms for public participation by broadcasting key aspects on national television and radio. In addition, the Presidency and almost all ministries, as well as public institutions, such the National Human Rights Commission, have social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, through which they communicate with the population on matters of public concern.

Social media not only facilitates the sharing of communication about mechanisms for public participation, but also serves to some extent as a platform itself for public participation. However, the impact of such efforts towards public engagement remains limited. This is why CSOs, such as the Centre d’information et de documentation (Cidoc), implements projects that aim to sensitize citizens at the local level about the various mechanisms for publication and trains local actors on strategies to enhance civic engagement and public participation.

Marginalized Groups

Article 12 of the Burkinabe Constitution provides that “all Burkinabe, without distinction, have the right to participate in the management of state and social affairs.” Article 11 of the Territorial Collectivities Code provides that every inhabitant of a territorial collectivity (i.e., a region or a commune) has the right to participate in local governance and local development decisions (italics added for emphasis). These legal provisions basically protect the participation of marginalized groups at both the national and local levels.

The participation of specific groups is also enhanced by human rights instruments that protect certain groups, such as women (e.g., The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol (2005)), youth (the African Youth Charter (2009)), and internally displaced people (IDP) (the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa, or the Kampala Convention (2012)), which Burkina Faso has ratified.

In addition, laws have been adopted to strengthen the protection of marginalized groups in the governance of public affairs. For instance, in order to encourage women’s political involvement, Law No. 003-2020/AN of January 2020 was adopted to establish quotas and procedures for having women candidates on legislative and municipal election lists. This law encourages political parties and organizations to take women into account in their lists of candidates for elected positions, even though there are still serious limits in terms of sanctions for non-compliance with that law. Discussions have been ongoing on how to reform this law to encourage better compliance.

Law No. 012-2010/AN of April 2010 on the protection and promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities also requires public authorities to take steps to ensure the participation of persons with disabilities in public governance at all levels. For instance, Article 40 of Section VIII of this law relates to “Participation in political and public life” and specifically states that “all persons with disabilities shall enjoy the same civil and political rights and shall exercise them on an equal basis with others and in accordance with the laws in force concerning legal capacity.”

Decree No. 2015-1037/PRES-TANS/PM/MJFPE/MEF of August 2015 envisions support for the socio-economic participation of youth through the Support Fund for Youth Initiatives (FAIJ). However, the impact of this decree has yet to be realized, given challenges to the operationalization of this fund. Perhaps of greater concern is the broader practice of excluding the youth from competing for key political positions in political parties.

Meanwhile, the rights of elderly persons to participate in public governance is guaranteed by law.

Environmental Advocacy

In the area of climate and environmental advocacy, there are no specific restrictions on civic participation. Article 8 of the Burkinabe Environmental Code states that “Local populations, non-governmental organizations, associations, civil society organizations and the private sector have the right to participate in the management of the project. They participate in the process of decision, elaboration, implementation and evaluation of plans and programs that affect their environment.” Article 9 of the Code further emphasizes the obligation of the government to facilitate civic participation by providing information: “… public authorities are required to facilitate access to information relating to the environment.” (italics added for emphasis)

Counter-Terrorism

The application of certain legal provisions relating to the security sector and the fight against terrorism have been criticized as undermining the right of professional groups, such as journalists and more generally people relying on media platforms, to participate in public debates. For example, Article 312-15 of the Penal Code imposes imprisonment for one to five years and a fine of one million (1,000,000) to ten million (10,000,000) CFA francs to any person who publishes or relays without authorization, by any means of communication whatsoever and regardless of the medium, images or sounds of a terrorist crime scene (italics added for emphasis). While the relevance of regulating the media space in the context of fight against terrorism cannot be overstated, the laws and regulations must be as specific as possible in order not to undermine the freedom of the press, which is a key ingredient of public participation. Further, the sanctions seem to be disproportionate to the potential harm they address.

In addition, during public demonstrations held on July 1, 2023, CSOs spread the message that “The legitimacy of Captain Ibrahim Traore and his government draws its source from the people of Burkina Faso.” They gathered under what is know as the National Coordination of CSOs of Burkina Faso. These CSOs have unequivocally expressed support to the current regime, and have been supporting the transitional government’s Action Plan (PA-SD) by promoting the project of a new constitution for the country. On other hand, there is another group of CSOs called the National Council of CSOs , which actually “denounced the usurpation of its acronym” by the former, and specifically stated that people should not be concerned with the aforementioned demonstrations organized on July 1, 2023 (both CSO groups use the acronym “CNOSC-BF”.

Indeed, there currently seem to be two groups of CSOs in Burkina Faso. The latter National Council seems to be more moderate than the former (National Coordination of CSOs), particularly insofar as publicly supporting the government’s actions. However, such a distinction seems not to be irrelevant for the government, which invited CSOs, including the above-mentioned CSO National Council, to a briefing session on the country’s security situation in the context of fight against terrorism. In this briefing, the Minister of Defense decried an “international coalition against Burkina Faso”.

All in all, unlike political parties, whose activities have been suspended indefinitely, CSOs remain very active. For example, they participate in public conferences about the transition, capacity building on civic participation, documentation of human rights violations, and public demonstrations as mentioned above.

BARRIERS TO FORMATION

According to Article 4 of Law 064, “Associations are formed freely and without prior administrative authorization. Their validity is governed by general contract law.” Furthermore, Article 13 affirms this freedom by stating that, “A receipt for the declaration of association is delivered by the relevant authority no later than two months afterwards, including the day of declaration. Beyond such a time period, silence from relevant authorities constitutes a declaration of the association’s existence and obligates the administration to provide a receipt for the declaration to facilitate publication formalities.” In practice, associations are often created and sometimes operate for several years before obtaining administrative recognition.

The conditions for creating and establishing associations are described in Articles 5 and 6, which state that, “Any person wishing to create an association with legal capacity must observe the following formalities:

- hold a board meeting;

- during that meeting submit for adoption the organizational plan and statutes governing the association (among other things, the organizational plan must mention the directors’ roles);

- establish board meeting minutes within the organizational plan, provide the identities and complete addresses of members and, if it exists, the association’s mailing address; and

- have board meeting minutes signed by the board members.”

Associations seeking legal capacity must submit an application to the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization, and Social Cohesion (MATD). The Directorate of Civil Society Organizations has a dedicated office within the MATD to receive all the required documentation.

Law 064 introduced a fee of 15,000 CFA (approximately 25 USD) as a registration fee, along with stamp fees charged for the legal filing of application documents.

Chapter 2, Title 5 of Law 064 outlines available sanctions. These sanctions mostly concern violations of stated procedures governing the association’s publication of its registration, declarations of changes in board membership, and refusals to apply a suspension or withdrawal of receipt by the administration. Articles 59 and 60 of Law 064 establish financial penalties for not abiding by certain rules of the law, which range from 500,000 CFA (approximately 800 USD) to 1,000,000 CFA (approximately 1,600 USD).

BARRIERS TO OPERATIONS

Article 16 of Law 064 expressly states that certain activities are illegal: “Associations founded for illegal purposes or aims contrary to law and proper mores are null and void. Equally null and void are associations whose purpose and practices go against the dignity of human persons or that advocate hate, intolerance, xenophobia, ethnocentrism or racism.” When an applicant association’s internal statutes and regulations reveal evidence of such illegal purposes or practices, the administrative authority can refuse to recognize an association. A list of the sanctions when associations’ activities violate laws can be found in Articles 58 to 65 in Chapter 2, Title 5 of Law 064.

The law does not allow the government to interfere in the management and operation of associations. In practice, there have been no reported cases of administrative interference in the management of associations’ or NGOs’ operations. Government agencies do not carry out arbitrary checks, nor do they harass NGOs with arbitrary inspections of their headquarters.

More concerning, however, is collusion by certain NGOs with governments or parties in power. After 2015, which was a year of political transition, the politicization of a part of civil society became more apparent, with NGOs called “specific movements” becoming openly partisan. NGOs believed to be close to political powers, for example, abstained from cooperating with other NGOs that were critical of the government. This phenomenon lessened somewhat with the return of elected political institutions in 2016.

Barriers to International Contact

Burkinabe laws place no restrictions on associations becoming members or partners of international or regional networks. Internet access is unrestricted in Burkina Faso and theoretically available to all citizens. That said, access to the Internet is too expensive for poorer citizens and the quality of internet access may be impeded by challenges with bandwidth and stability.

BARRIERS TO RESOURCES

Foreign Funding

No legal or regulatory provisions restrict associations or NGOs from accessing foreign funding. In fact, a large percentage of funding for association and NGOs comes from foreign sources. There is concern, however, that the Burkinabe government exerts pressure to ensure certain associations and NGOs do not receive funding through international cooperation or from international development institutions in an effort to reduce the impact of independent voices in the country.

Domestic Funding

Law 064 does not prohibit NGOs from engaging in economic activities. The only restriction is the notion of “not-for-profit,” which does not prevent NGOs from engaging in economic activities, but rather concerns the use of revenue generated by such activities. Certain NGOs like Association pour les Initiatives Locales based in Kaya and VARENA ASSO in Diébougou have well-developed economic activities.

Ministerial officials charged with recognizing associations sometimes ask certain associations to refrain from revenue-generating activities because they do not understand the law or the nature of not-for-profit associations.

In order to continue to receive funding, most NGOs practice self-censorship on sensitive subjects. In early 2019, self-defense militias from the Koglweogo movement and members of the armed forces were involved in multiple massacres, leading to at least 500 deaths in only two months. Very few NGOs and activists mentioned these summary executions, however, or participated in press conferences. The vast majority of NGOs remained silent rather than risk being labeled opposition organizations and having their funding cut.

Philanthropy, sponsorship, and corporate social responsibility are not well-developed in Burkina Faso and thus corporations rarely provide domestic funding to NGOs.

BARRIERS TO EXPRESSION

Article 8 of the Constitution of June 2, 1991, states “Freedom of opinion, press and the right to information are guaranteed. All persons have the right to express themselves and to broadcast their opinions within the confines of existing laws and regulations.”

Areas related to freedom of expression, such as the freedom of information, also benefit from constitutional protection. Media agencies are usually freely created, and the procedures for establishing them are straightforward.

The regulation of social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) began in 2015 through Law 058/2015, which regulates professional online media services. Some of its provisions contain overbroad terms that could make their enforcement problematic. The law imposes vague conditions on “professional” online media services; for example, the media service is required to avoid content that can shock or undermine human dignity or decency. The law provides for penalties that are problematic due to overbroad offences like “false news”. Administrative offences like “not properly declaring one’s service” or operating without accreditation (for foreign services) are subject to substantial fines.

Since 2016, government supporters have targeted NGOs and media on social networks, and certain activists have been thrown in prison for expressing themselves on subjects of national importance. Cyber-activist Naïm Touré, for example, spent over two months in prison in 2018 for his post about a police officer being wounded in a counter-terrorism operation.

In July 2019, the government passed an important modification of the penal code that limited freedom of expression, particularly on social media, but also traditional media, by making “fake news” illegal. The limitations were denounced by many organizations, such as Reporters Sans Frontières, Human Rights Watch, and the Committee to Protect Journalists.

This amendment of the Penal Code, which is intended to facilitate the fight against terrorism by strengthening the control of the content of information primarily in connection with national security, has been subject of criticism for creating barriers to speech. For instance, Article 312-14 provides that one “shall be punished by a prison sentence of one to five years and a fine of one million (1,000,000) CFA francs to ten million (10,000,000) CFA francs whoever communicates, publishes, discloses or relays through a means of communication, regardless of the medium, information relating to the movement, geographical position, weapons and means of the defense and security forces, sites, facilities of national or strategic interest likely to undermine public order or the security of persons and property”. In the same spirit, Article 312-11 states: “Any person who, in peacetime, knowingly participates, by any means whatsoever, in an enterprise to demoralize the Defense and Security Forces shall be punished by imprisonment for a term of one year to ten years and a fine of three hundred thousand (300,000) to two million (2,000,000) CFA francs”. Like Articles 312-13, 312-15 and 312-16 of this law, the above provisions have been criticized by CSOs for “criminalizing the activities of human rights defenders, journalists, social networkers and any individual who wants to gather or disseminate information, particularly on facts related to military operations”. Indeed, for most many human rights and journalists’ organizations, some provisions of the Penal Code can disproportionately restrict civic participation in the governance of the security sector. However, very little or no information exists regarding case law specifically concerning these provisions of this Code, and their impact on public or civic participation.

Furthermore, Burkinabe law very clearly separates associations from political parties. Article 7 of Law 064 states, “Leading members of an association cannot be leading members of political parties.” In practice, this provision has limitations. For example, a member or leader of an association may participate in some party activities, such as helping to draft a proposal for legislation or a political platform, without being part of the party leadership or public.

BARRIERS TO ASSEMBLY

The Burkinabe Constitution recognizes the freedom of assembly and demonstration. Article 7 states, “The freedom to believe, not to believe, of conscience, religious opinion, philosophy, religious practice, freedom of assembly, practice of customs as well as the freedom of procession and demonstration are guaranteed by the current Constitution, on condition that law, public order, proper mores and human persons are respected.”

Advance Notification

Law No. 22/97 implementing the Constitutional provision on freedom of assembly requires that demonstrations receive prior authorization, stating, “Public gatherings must receive prior authorization when such gatherings include a conference or exposé, on any subject, followed by a debate or not; they must adhere to conditions set by Articles 8 and 9 below. Advance notification must be written and addressed to the relevant administrative authority. This authority may, for reasons of public order, forbid the gathering.”

This provision is affirmed by Article 10, which states “Any procession, parade, gathering of persons and, generally, any public demonstration must provide advance notification addressed to the Ministry for Public Liberties whenever the demonstration is of a national or international nature, and to the Head of the District Administration or municipality concerned in other cases… It may, if circumstances require it, declare the demonstration be banned.” Thus, a freedom granted by the Constitution as a political right of citizens is made dependent on approval by an administrative authority.

An organizer must contact the Ministry for Public Liberties (ministre chargé des libertés publiques) to hold a demonstration of a national nature, while local authorities, usually the mayor of the community, are responsible for local demonstrations. Demonstration organizers must submit an application for prior authorization at least 72 hours before the planned demonstration. They are also held responsible for anything that happens during the demonstration. Authorities must make their decision known at least 24 hours before the demonstration (Article 10). Organizers must take measures to prevent violence during the demonstration or else they will be held responsible for such violence.

Time, Place, and Manner Restrictions

In practice, the right to demonstrate is largely restricted by administrative authorities who have great power to permit or forbid the exercise of the right. Article 12 of Law No. 22/97/II states, “The administrative authority may, at any moment, without having previously issued a ban, put an end to any gathering, procession, parade or public assembly in the interest of public order.” At times, administrative authorities’ decisions have been colored by political or partisan biases.

Since 2013, certain streets and squares in the capital Ouagadougou have been classified as “red zones” and have been closed off to demonstrations.

It has been noted that demonstrations organized by those considered “opponents” of the government are the ones most likely to be banned. The Framework for Democratic Expression (CED), for example, was denied the right to hold a demonstration in November 2017, and its leader, Pascal Zaida, was incarcerated for two months in Ouagadougou. The CED is known for its strong views accusing political leaders and the present government of crimes.

Excessive Penalties

Articles 14 and 15 of the 1997 law set criminal sanctions for acts tied to the freedoms of demonstration and assembly. Article 14, for example, states, “When by concerted action and open force by a group, violence, assault or illegal confinement of persons or destruction or damage of property, real or personal, public or private, occurs, instigators and organizers of the action, as well as willing participants, will be punished by imprisonment of two (2) to five (5) years and fined 500,000 (approximately $800) to 1,000,000 (approximately $1,600) CFA.”

The penalty does not target the perpetrators of violence, but instead the demonstration organizers. A very well-known application of these provisions took place in 1999 during demonstrations by the Movement for Truth and Justice to support Norbert Zongo, an investigative journalist who was burned to death on October 13, 1998. Leaders of his collective were arrested and imprisoned and their heads shaven after a non-violent demonstration.

In 2017, Pascal Zaida, an activist, was also arrested and imprisoned for organizing a march followed by a meeting that had not received prior authorization by the city’s mayor. Based on the prison sentences in Articles 14-21 of Law 22/97, Pascal Zaida was incarcerated in November 2017 after the demonstration he planned was canceled.

Generally speaking, however, the police do not use excessive force to maintain order. Certain demonstrations are high-risk due to their political nature and the country’s political history, which has seen peaceful demonstrations turn into popular uprisings that led to the overthrow of governments (January 6, 1966 and October 30, 2014, for example). Police sometimes use tear gas to disperse demonstrators, particularly in the context of student demonstrations. Incidents of police assaulting demonstrators are rare, but have occurred.

Additional Resources

GLOBAL INDEX RANKINGS

| Ranking Body | Rank | Ranking Scale (best – worst possible) |

|---|---|---|

| UN Human Development Index | 186 (2023) | 1 – 193 |

| World Justice Project Rule of Law Index | 98 (2024) | 1 – 142 |

| Fund for Peace Fragile States Index | 21 (2024) | 179 – 1 |

| Transparency International | 82 (2024) | 1 – 180 |

| Freedom House: Freedom in the World | Status: Not Free Political Rights: 3 Civil Liberties: 22 (2025) | Free/Partly Free/Not Free 40 – 0 60 – 0 |

REPORTS

| UN Universal Periodic Review Reports | Burkina Faso UPR page |

| Reports of UN Special Rapporteurs | Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism: Mission to Burkina Faso |

| U.S. State Department | 2024 Human Rights Report: Burkina Faso |

| Fragile States Index Reports | Burkina Faso |

| IMF Country Reports | Burkina Faso and the IMF |

| International Court of Justice | Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Mali) |

| International Center for Not-for-Profit Law Online Library | Burkina Faso |

NEWS

Burkina Faso protests US response to HRW massacre report (May 2024)

Britain and the United States said they were “gravely concerned” a few days after HRW published a report accusing soldiers of killing at least 223 people, including 56 children, in revenge attacks on two villages on February 25. London and Washington jointly urged Ouagadougou to “thoroughly investigate these massacres and hold those responsible to account”. The military rulers of Burkina Faso dismissed the report as “baseless” and suspended a swathe of international news organisations for airing accusations of an army massacre of civilians, including the British BBC and the US Voice of America.

Civil society calls for release of Daouda Diallo abducted human rights defender (December 2023)

A major coalition of West African NGOs demanded the “immediate release” of Daouda Diallo, the Burkina Faso human rights defender abducted in Ouagadougou by men in plain clothes. The organization “demands the immediate and unconditional release of Dr Daouda Diallo, as well as guarantees of his physical and psychological integrity”.

Emergency Law Targets Dissidents (November 2023)

Burkina Faso’s military junta is using a sweeping emergency law against perceived dissidents to expand its crackdown on dissent, Human Rights Watch said. Between November 4 and 5, 2023, the Burkinabe security forces notified in writing or by telephone at least a dozen journalists, civil society activists, and opposition party members that they will be conscripted to participate in government security operations across the country.

NGO says Karma ‘massacre’ death toll is at least 136 (April 2023)

A Burkinabe human rights organization counted 136 civilians, including 50 women and 21 children, killed on April 20 in the village of Karma in northern Burkina Faso by men wearing army fatigues…. In Karma, “they grouped civilians by the dozens and by neighborhoods, taking care to assign armed men to each grouping, with the slogan: ‘Kill everyone,’” said CISC President Daouda Diallo, winner of the 2022 Martin Ennals Prize, the “Nobel Prize” for human rights.

ARCHIVED NEWS

Burkina Faso and Global Fund Launch New Grants to Accelerate Progress against HIV, TB and Malaria (February 2021)