Recent Developments

On May 20, 2025, the Legislative Assembly, which is controlled by President Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party, passed the Foreign Agents Law without meaningful public debate or consultation. The Law requires people and organizations that receive funding from abroad to register as “foreign agents” with a newly established Foreign Agents Registry under the Interior Ministry. While presented as a transparency measure, in practice it grants the government broad powers to control, stigmatize, and sanction human rights organizations that receive international support. Please see the Barriers to Resources and News sections below for additional details.

While we aim to maintain information that is as current as possible, we realize that situations can rapidly change. If you are aware of any additional information or inaccuracies on this page, please keep us informed; write to ICNL at ngomonitor@icnl.org.

Introduction

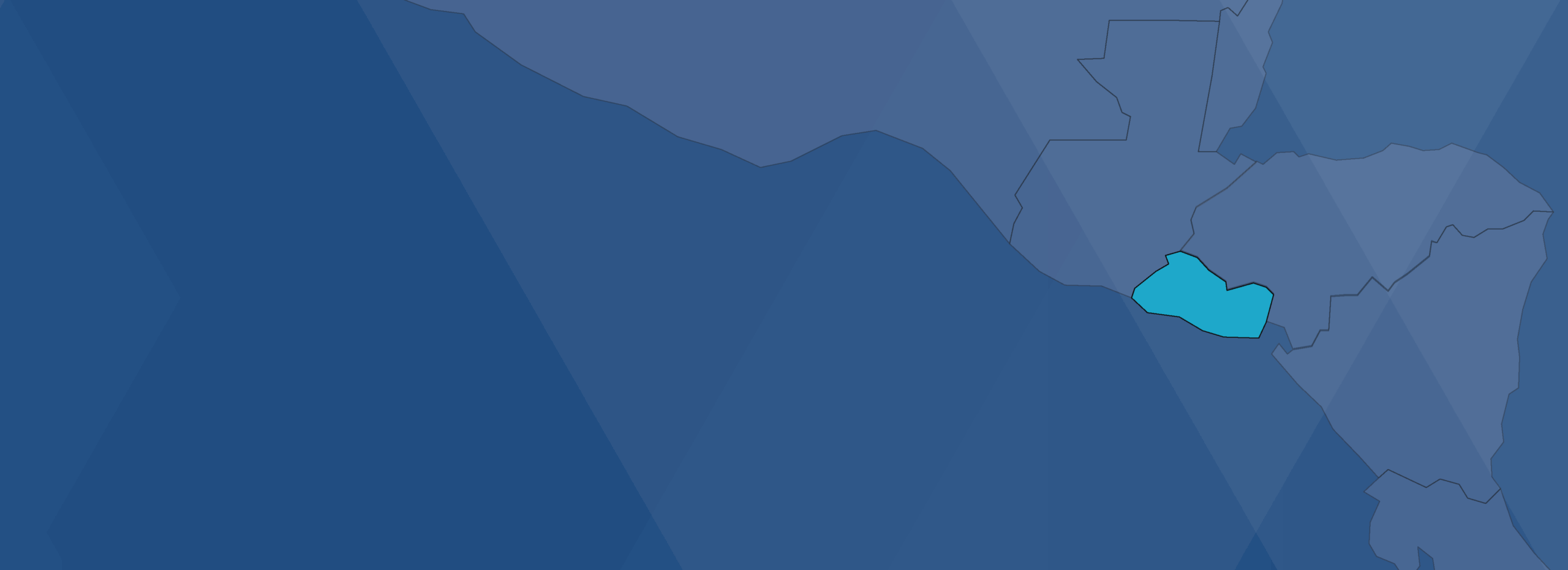

Civil society in El Salvador has deep historical roots, beginning with humanitarian organizations in the 1960s and later expanding to include service provision, human rights advocacy, and policy development.

The legal framework governing civil society is rooted in El Salvador’s civil law tradition. It is established primarily by Article 7 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right of association and assembly for lawful purposes, and the 1996 Not-for-Profit Foundations and Associations Law (LAFSL), which regulates the establishment and operation of CSOs.

Despite these formal guarantees, civic space in El Salvador remains under significant pressure, particularly for organizations engaged in human rights and government accountability work. CSOs face burdensome oversight. Freedom of expression is constrained by smear campaigns against rights-based organizations, while freedom of assembly is restricted through vague criminal provisions, discretionary enforcement, and repeated extensions of emergency measures.

Civic Freedoms at a Glance

| Organizational Forms | Associations and Foundations at the national level and Development Associations at the local level |

| Registration Body | Associations and Foundations: Registry of Non-Profit Associations and Foundations, attached to the Ministry of Governance and Territorial Development Development Associations: Municipal Councils |

| Approximate Number | Associations and Foundations: 4,484 registered organizations, including 3,356 associations and 1,128 foundations (as of July 14, 2021) Development Associations: Unknown. El Salvador has 262 municipalities, each of which maintains an individual registry of community development associations. |

| Barriers to Formation | Associations and Foundations: CSOs have been stigmatized and viewed as opponents for demanding respect for human rights and El Salvador’s Constitution. Development Associations: Because of political party interests, there are community associations that whenever there is a change in local government are not recognized by the local authorities for conducting development initiatives, despite having legal status. |

| Barriers to Operations | Associations and Foundations: CSOs have been stigmatized and viewed as opponents for demanding respect for human rights and El Salvador’s Constitution. Development Associations: Because of political party interests, there are community associations that whenever there is a change in local government are not recognized by the local authorities for conducting development initiatives, despite having legal status. |

| Barriers to Resources | Associations and Foundations: No public grants exist for the work and development of CSOs. Funds are allocated to CSOs by the Legislative Assembly according to political interests. The “Special Commission to investigate funds granted to NGOs” has been established. Development Associations: A lack of political party affinity between community associations and local authorities leads the latter to not fund development initiatives in certain communities. All Organizations: “Foreign agents” required to register with Foreign Agents Registry under the Interior Ministry, which grants the government broad powers to control, stigmatize, and sanction human rights organizations that receive international support. |

| Barriers to Expression | The work of social organizations is widely stigmatized and CSOs are labelled as “front organizations” that are “used to divert public funds and enrich political figures.” |

| Barriers to Assembly | Broad discretion for authorities to determine what is a “lawful” purpose; additional restrictions during election periods; terrorism laws used arbitrarily against protesters. |

Legal Overview

RATIFICATION OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

| Key International Agreements | Ratification* |

|---|---|

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) | 1979 |

| Optional Protocol to ICCPR (ICCPR-OP1) | 1995 |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) | 1979 |

| Optional Protocol to ICESCR (Op-ICESCR) | 2011 |

| International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) | 1979 |

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) | 1981 |

| Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women | No |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) | 1990 |

| International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) | 2003 |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) | 2007 |

| Key Regional Agreements | Ratification |

|---|---|

| Organization of American States (OAS) | 1950 |

| American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) | 1978 |

| Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (“Protocol of San Salvador”) | 1995 |

* Category includes ratification, accession, or succession to the treaty

CONSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

El Salvador is a unitary state that follows the civil law tradition. The Constitution, as the supreme law of the land, regulates the rights and duties of all of the country’s inhabitants. It protects the rights to freedom of expression and thought, as well as the freedom of association.

Article 7 of the Constitution states that:

The inhabitants of El Salvador have the right to associate freely and to meet peacefully, without arms, for any lawful purpose. Nobody shall be obligated to belong to an association.

A person shall not be limited or impeded from the exercise of any licit activity because he does not belong to an association.

The existence of armed groups of a political, religious or guild character is prohibited.

In accordance with Article 240 (5) of the Constitution, municipalities can approve the formation of community associations through the authority that has been conferred on them to promulgate local ordinances and regulations. Secondary legislation regulates the scope of the rights articulated in the Constitution. The Vice President of El Salvador, Felix Ulloa, together with a team of lawyers, has prepared a list of constitutional reforms that would represent a modification of 85% of the 1983 Constitution. Article 7 is included among the anticipated reforms.

NATIONAL LAWS, POLICIES, AND REGULATIONS

Civil society organizations (CSOs) in El Salvador are governed by (1) the 1996 national-level Law for Not-for-Profit Associations and Foundations [Ley de Asociaciones y Fundaciones sin Fines de Lucro] (LAFSFL), which regulates the establishment, operation, and dissolution of CSOs; and (2) the Municipal Code and municipal ordinances issued by each of the country’s 262 municipalities. The goal of the local-level regulation is to promote effective CSO engagement at the local level to address public policy priorities. According to Article 118 of Title IX of the Municipal Code, “Municipal governments are obligated to promote citizen participation, provide public information on municipal management, address matters that residents may request, and those that the Council considers convenient.”

Additional laws that may affect civil society include:

- Código Municipal (Municipal Code)

- Código Penal (Penal Code)

- Ley de Proscripción de maras, pandillas, agrupaciones, asociaciones y organizaciones de naturaleza criminal (Prohibition Act of maras, gangs, groups, associations and organizations of a criminal nature)

- Ley Especial contra actos de terrorismo (Special Law against Acts of Terrorism)

- Ley General de Juventud (General Law of Youth)

- Ley Marco para la Convivencia Ciudadana y Contravenciones Administrativas (Framework Law for Coexistence and Administrative Violations)

- Ley Penitenciaria (Penitentiary Act)

- Ley Contra el Lavado de Dinero y de Activos (Law Against Money Laundering)

- Ley de Firma Electronica (Electronic Signature Law)

- Reformas de Ley de Telecomunicaciones (Reforms of Telecommunications Law)

- Ley Contra el Lavado de Dinero y de Activos (Anti-Money Laundering Act)

- Ley de Desarrollo y Protección Social

- Reglamento de la Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública

- Reglamento General de la Ley del Medio Ambiente

- Instructivo de la Unidad de Investigación Financiera – Fiscalía General de la República de El Salvador

PENDING REGULATORY INITIATIVES

Please help keep us informed; if you are aware of other pending initiatives, write to ICNL at ngomonitor@icnl.org.

Legal Analysis

ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS

The Not-for-Profit Associations and Foundations Act (LAFSFL) establishes two categories of CSOs (Article 1), which may be domestic or foreign (Article 44):

- Associations are private legal entities formed by two or more natural or legal persons for the ongoing pursuit of any legal not-for-profit activities (Articles 9 and 11). They are established through public instruments executed by the founding members and governed by internal bylaws. Their members may be natural or legal persons who are nationals or foreigners, although foreign members must reside in the country (Article 12). The bylaws define members’ rights and obligations and conditions of membership (Article 14). Federations and confederations of legal persons are also recognized as associations (Article 17).

- Foundations are non-membership organizations created by one or more natural or legal persons, which can be nationals or foreigners, to manage capital intended for public service (Article 18). They must have both an endowment and operating funds at the time of establishment (Article 22). Foundations are created through a public instrument or will (Article 19) and governed by internal bylaws (Article 23).

Both associations and foundations obtain legal status by registering with the Ministry of the Interior and Territorial Development (Article 26). As of July 14, 2021, there were 4,484 registered organizations, including 3,356 associations and 1,128 foundations.

The Municipal Code (Código Municipal (MC)) recognizes two additional categories of CSOs at the local level:

- Municipal associations,which are created by and attached to municipalities (Article 12). Their legal status is granted by the municipality in their articles of incorporation.

- Community associations, which are formed by at least 25 local residents to address common needs (Article 118-120). They require a decision by a special general assembly for their establishment, while the relevant municipal council grants them legal status (Article 119).

Certain organizations fall under separate legal regimes. Churches are governed by Articles 542 and 543 of the Civil Code (Código Civil), while trade unions are regulated under the Labor Code (Código del Trabajo). Neither churches nor trade unions are addressed elsewhere in this report.

PUBLIC BENEFIT STATUS

Associations and foundations may be declared public interest entities, upon certification by the General Directorate of Internal Taxes under the Ministry of the Treasury. This designation, which is sought by nearly all CSOs, grants exemption from income tax. This benefit is regulated by the LAFSFL (Articles 6 and 7) and the Income Tax Act (Ley del Impuesto sobre la Renta) (Article 6).

To qualify, CSOs must be established for the purposes of social assistance, promotion of road building, charity, education and instruction, cultural, scientific, literary, artistic, political, or sports activities; business associations and trade unions are also eligible. In addition, their income and assets must be used exclusively to advance the organization’s purposes and may not be distributed among their members (Income Tax Act, Article 6). In practice, however, the process of obtaining this status is long and bureaucratic.

The law does not establish explicit criteria for certifying public interest status, leaving significant room for arbitrary interpretation. In addition, the regulations provide no appeals procedure for organizations whose applications are denied. As a result, CSOs that are refused public interest status have no recourse other than initiating lengthy and costly legal proceedings.

Public interest status is granted for one year and renews automatically absent a notice of revocation from the tax authorities. The designation may be revoked if the conditions under which it was granted are no longer met (LAFSFL, Article 7). Neither the LAFSFL nor tax laws establish a clear procedure for revoking eligibility, and there are no known cases of revocation.

Designation as a public interest entity does not exempt the CSO from fulfilling other formal obligations, such as submitting reports and other documentation requested by the tax authorities.

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

Article 18 of the Constitution recognizes that “[e]very person has the right to address written petitions…to the legally established authorities; and to have such petition resolved and to be informed of the result.” Several laws aim to implement this right.

Municipal Code

The Municipal Code (1986) requires municipalities to promote citizen participation (Article 115). It outlines numerous participatory mechanisms such as public meetings of municipal councils, open town halls, popular consultations, neighborhood and sectoral consultations, participatory investment plans and budgets, local development committees, and citizen security councils (Article 116). Article 118 further allows residents to form community associations to address community problems and needs, although such associations must have at least 25 members to obtain legal status. This high membership threshold inhibits the formation of small community associations.

Framework Act for Civic Coexistence and Administrative Contraventions

The Framework Act for Civic Coexistence and Administrative Contraventions (Ley Marco para la Convivencia Ciudadana y Contravenciones Administrativas) (2011) seeks to promote citizen security, preserve the full enjoyment of public and private spaces in municipalities, and stimulate civic engagement (Article 2(a)). While it also requires municipalities to promote participation (Article 15), it repeats the requirement that community development associations (ADESCOs) have at least 25 people (Article 120), mirroring the Municipal Code.

Internal Regulations of the Legislative Assembly

The 2005 Internal Regulations of the Legislative Assembly (El Reglamento Interior de la Asamblea Legislativa (RIAL)) provide for hearings and consultations by legislative committees to give voice to those interested in or affected by legislative bills. Citizens may also address the full Assembly by submitting a written petition. If approved, they may only speak on the issues specified in their request (Article 78).

Social Development and Protection Act

The 2014 Social Development and Protection Act (Ley de Desarrollo y Protección Social) requires the government’s Social Development, Protection and Inclusion Plan to be developed through participatory mechanisms and include intersectoral coordination and social participation in its monitoring (Articles 12-20). In practice, however, the current Cuscatlan Plan was presented by President Nayib Bukele before his inauguration, with little or no public consultation.

Freedom of Public Information Act

The 2011 Freedom of Public Information Act (Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública (LAIP)) obliges public bodies and agencies, autonomous institutions, municipalities, and other entities that administer public resources and state assets to publish information, including mechanisms for citizen participation and accountability (Article 10(21)). In addition, LAIP mandates the Institute for Freedom of Public Information (Instituto de Acceso a la Información Pública (IAIP)) to promote a culture of transparency. LAIP regulations also foresee CSO participation as observers of election procedures, where possible (Article 62). In practice, however, the Act’s impact has been undermined by President Nayib Bukele’s open stigmatization of CSOs.

Environmental Act

The 1988 Environmental Act (Ley de Medio Ambientes) guarantees people’s right to be informed and consulted on environmental issues and established participatory mechanisms such as the National Council on Environmental Sustainability and Vulnerability and the Sustainable El Salvador Plan. Yet, under the Bukele administration, communities have often been excluded from consultations, and environmental permits have been granted for construction projects in protected areas or sites of indigenous cultural heritage.

Act of the Salvadoran Institute for Women’s Development

The 1996 Act of the Salvadoran Institute for Women’s Development (Ley del Instituto Salvadoreño para el Desarrollo de la Mujer) provides for equal rights and women’s full participation on equal terms with men in all spheres of society, including decision-making processes and access to power. The Act also called for the creation of the Salvadoran Institute for Women’s Development (ISDEMU) to design, direct, carry out, advise, and ensure compliance with the National Women’s Policy and promote the holistic development of Salvadoran women.

BARRIERS TO FORMATION

Although the law does not prohibit the formation and operation of unregistered groups that work towards legal purposes, CSOs in El Salvador face multiple barriers at the formation stage, ranging from vague legal provisions to excessive costs and administrative delays.

To register, an organization submits a written application to the Directorate General of the Registry of Not-for-Profit Associations and Foundations (RAF). The application should include three copies of the public instrument containing the articles of incorporation and bylaws, the election of the first board of directors or governing board, and other documentation (LAFSFL, Article 65).

Vague Grounds for Denial

Under the LAFSL, RAF may deny registration if an organization’s objectives are deemed contrary to “public policy, morality, and good customs.” These undefined terms invite subjective interpretation and give the government wide discretion to impede or delay registration. However, the Constitutional Division of the Supreme Court of Justice declared this provision unconstitutional (8-97Ac, 2001).

RAF Overstepping its Authority

RAF often oversteps its authority by coordinating with line ministries or other relevant public agencies to review applications. These entities may object to the CSO’s bylaws or other constitutional documents or demand modifications, while RAF itself makes recommendations on form and style. Applicants may be asked to narrow broad objectives or provide detailed information about funding sources. Such requirements, which are not explicitly set out in law, impose burdens on CSOs and create legal uncertainty.

Appeals

If registration is denied, an applicant may file an administrative appeal with the Ministry of the Interior and Territorial Development (MIGOB) within three business days. MIGOB must issue a decision within 15 business days. This decision is final (LAFSL, Article 51).

Excessive Costs

Establishing a CSO is costly. Beyond the fixed registration fee of approximately $35 (LAFSL, Article 69), applicants must cover expenses such as:

- A notary to draft incorporation papers ($300-600, although this is sometimes done for free);

- An auditor to certify the CSO’s initial balance ($30);

- Publication of the CSO’s articles of incorporation in the Official Gazette (approximately $85 for 30 articles); and

- An order or decree confirming the CSO’s legal status (around $30).

Altogether, these requirements bring total costs to between $500 and $800. However, if assisted by an attorney or notary who files the papers with RAF, as is often the case, costs can reach upwards of $2,000, including filing fees and the purchase of mandatory record books.

Non-Adherence to Time Limits

By law, RAF must notify applicants of deficiencies in their applications within 90 business days. The notification should specify the errors or violations and advise the organization how to correct them. Organizations then have 45 business days to submit corrected documentation (LAFSL, Article 65) and another 10 business days under Articles 83 and 88 of the Administrative Procedures Act (Ley de Procedimientos Administrativos).

In practice, these deadlines are frequently ignored. Some organizations wait years for approval, while others are fast-tracked, often due to political considerations. Delays may also stem from applicants failing to correct deficiencies on time.

Delays at the Municipal Level

Community associations register with municipal councils, which are legally required to decide on applications within 15 days. If there is an objection, the applicant is given 15 days to make corrections. The Council must issue a decision within 15 days from the date of the new application.

If no decision is issued within the 15-day time frame, the law mandates automatic approval and registration, with publication in the Official Gazette. In practice, municipalities often disregard these requirements, leading to inconsistent and delayed registration of community associations.

BARRIERS TO OPERATIONS

Criminalization of Associations

Article 345 of the Criminal Code classifies as criminally illicit any group or association that:

- Consists of three or more people, whether temporary or permanent, de facto or de jure, and is formed for the purpose of committing a crime; or

- Falls within the scope of Article 1 of the Law for the Prohibition of Posses, Gangs, Groups, Associations and Organizations of a Criminal Nature.

Sanctions are also imposed on members of terrorist organizations. Article 13 of the Special Law Against Acts of Terrorism imposes prison sentences of 8-12 years for participants in terrorist organizations and 10-15 years for leaders.

In recent years, reforms to the Criminal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code have impacted the right of association and criminalized human rights defenders. Ambiguous terms such as “associations” and “illicit groups,” combined with the prolonged Exceptional Regime, have facilitated mass arrests. (See also the Barriers to Assembly section below).

Barriers to International Contact

The LAFSL grants foreign CSOs the same rights as domestic CSOs, provided their purposes are lawful (Article 44). However, they are explicitly prohibited from engaging in “political activities” (Articles 44 and 47), a term left undefined in the law.

In 2020, the government created the El Salvador Agency for International Cooperation (ESCO-El Salvador), designating it as the sole authority for managing development cooperation. By centralizing all cooperation under the Presidency, the agency has increased risks of opacity in the allocation and use of resources. It also holds broad discretion to exclude or marginalize CSOs.

BARRIERS TO RESOURCES

Economic Activities

CSOs may engage in any lawful commercial or economic activity that is related to their organizational purposes. The only restriction is that the income must be used for institutional objectives and may not result in the direct enrichment of members, founders, or administrators (LAFSFL, Article 9).

Foreign Funding

In May 2025, the Legislative Assembly—controlled by President Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party—passed the Foreign Agents Law without meaningful debate or public consultation. The Law requires people and organizations that receive funding from abroad to register as “foreign agents” with a newly established Foreign Agents Registry under the Interior Ministry. While presented as a transparency measure, in practice it grants the government broad powers to control, stigmatize, and sanction human rights organizations that receive international support. The Law:

- Defines a “foreign agent” as any person or entity that “responds to the interests of, or is controlled or financed, directly or indirectly, by a foreign principal.” A “foreign principal” is broadly defined as any person or entity based abroad, including foreign governments, political parties, or organizations, as well as “people determined by the Foreign Agents Registry to fall under this category.”

- Imposes sanctions, including fines and the suspension or cancellation of legal status, on anyone who fails to register as a foreign agent.

- Levies a 30 percent tax on all foreign funding, including donations, goods, and services, with limited exemptions.

- Prohibits registered foreign agents from engaging in vaguely defined “activities with political or other purposes” that have the “objective” of “affecting the public order” or “threatening the social and political stability of the country.”

- Requires organizations receiving foreign funds to label their communications as “transmitted on behalf of” or “financed by” foreigners.

Public Funding

In May 2021, the Legislative Assembly established a “Special Commission to Investigate the Destination of Funds Granted to Non-profit Organizations, Associations and Foundations.” The Commission, which was initiated by deputies from the ruling Nuevas Ideas party, will investigate CSOs that have received state funds in previous years. The Commission’s creation was accompanied by stigmatizing public statements that accused CSOs of lacking transparency. These attacks failed to distinguish between organizations that received public funds through transparent processes and those that have never been publicly funded. This rhetoric has contributed to growing public mistrust of CSOs, particularly those engaged in human rights defense.

Anti-Money Laundering/Counter-Terrorism Financing

The Attorney General’s Office, through the Financial Investigation Unit (FIU), has also imposed new compliance obligations on CSOs through the “Instructions for the prevention, detection and control of money and asset laundering, financing of terrorism and the financing of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction,” which entered force in July 2023. In addition to requiring CSOs to register with FIU in a generally applicable way, they also require a risk assessment of the sector and a risk-based approach based on Recommendations 1 and 8 of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

BARRIERS TO EXPRESSION

Article 6 of the Constitution provides that every person has the right to express and disseminate their thoughts, provided that doing so does not disturb public order or harm the “morals, honor, or private lives of others.” The Constitution prohibits prior censorship and states that those who abuse this right in violation of the law will be held legally responsible for these offenses.

Despite these guarantees, CSOs report restrictions on their freedom of expression through defamation, insults, and slander, particularly when their positions differ from those of the government. Government officials, including President Nayib Bukele, frequently accuse CSOs of acting as fronts for political opposition parties or of receiving funding from unspecified foreign sources.

BARRIERS TO ASSEMBLY

Article 7 of the Constitution recognizes the right of the people of El Salvador “to freely associate and to assemble peacefully without weapons for any lawful purpose.” The absence of a clear definition of “lawful” leaves broad discretion to the authorities in determining permissible assemblies.

Advance Notification Requirements

Under Articles 181-183 of the Electoral Code, organizers of meetings or demonstrations with “electoral propaganda purposes” must apply in writing to the municipal mayor or city clerk for authorization at least one day in advance. The mayor must respond within 24 hours. If the application is approved, the National Civil Police and contending political parties or coalitions are notified. If denied, the denial must be based on a prior request for the same date, in which case another date is granted. This requirement applies only to demonstrations with an electoral purpose.

Counter-Demonstrations

Counter-demonstrations are de facto prohibited by the Electoral Code, as authorization must be denied if a prior request has already been submitted for the same date and location.

Spontaneous Demonstrations

Despite the notification requirements in the Electoral Code, the Constitutional Court ruled that spontaneous demonstrations are permitted. In Judgment 4-94 of June 13, 1995, the Court clarified that freedom of assembly is a fundamental right that cannot be conditioned on prior approval by the state. Limitations are permissible only if justified and established by law, thereby affirming the legality of spontaneous demonstrations.

Content Restrictions

Article 232 of the Electoral Code imposes restrictions on propaganda during political assemblies. It prohibits painting political propaganda on public or private property without permission and bars the use of symbols, colors, slogans, marches, or images associated with other political parties or coalitions.

Criminal Penalties

The Special Law Against Acts of Terrorism contains vague language that may be arbitrarily applied to assemblies. Article 6 criminalizes the occupation of cities, villages, public or private buildings, or public places using weapons, explosives, or similar articles. Violators of this provision are subject to 20-30 years of imprisonment. In 2007, terrorism charges including 10-15 year prison sentences were brought against protesters accused of blocking roads and throwing stones.

COVID-19 Restrictions

In mid-March 2020, the government declared a one-month state of emergency and adopted a decree-law restricting freedom of movement and assembly in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Public gatherings were limited to religious, cultural, economic, or sports purposes and required prior authorization from health authorities. The decree-law also suspended non-essential administrative and judicial functions, including access to public information.

Legislative Decree No. 90 of July 13, 2021, introduced “Special and Temporary Provisions for the Suspension of Concentrations and Public or Private Events” in response to another wave of Covid-19 infections. Initially, this applied to concerts, sporting events, and religious festivals, while marches were not explicitly restricted. Subsequent attempts were made to extend these restrictions to demonstrations, but President Bukele declined to sanction the extensions, citing expiration of the original decree.

Exceptional Regime

On March 27, 2022, the Legislative Assembly approved Legislative Decree No. 333, which established an “Exceptional Regime” in the country for 30 days in response to a peak in gang violence. The Decree, based on Article 29 of the Constitution, suspended rights to freedom of association, assembly, and privacy of communications, as well as certain due process guarantees. Between March and November 2022, more than 58,000 people were reportedly detained under the regime. Although Article 29 allows only one renewal, the Assembly repeatedly extended the regime through mid-May 2025.

Additional Resources

GLOBAL INDEX RANKINGS

| Ranking Body | Rank | Ranking Scale (best – worst possible) |

|---|---|---|

| UN Human Development Index | 132 (2023) | 1 – 193 |

| World Justice Project Rule of Law Index | 111 (2024) | 1-142 |

| Transparency International | 130 (2024) | 1 – 180 |

| Fund for Peace Fragile States Index | 85 (2024) | 179 – 1 |

| Freedom House: Freedom in the World | Status: Partly Free Political Rights: 17 Civil Liberties: 30 (2025) | Free/Partly Free/Not Free 40 – 0 60 – 0 |

REPORTS

| UN Universal Periodic Review Reports | El Salvador UPR page |

| Reports of UN Special Rapporteurs | El Salvador |

| U.S. State Department | Country report on human rights practices (2024) |

| Fragile States Index Reports | El Salvador |

| IMF Country Reports | El Salvador and the IMF |

| New York City Bar | Statement of Concern Regarding the Foreign Agents Law in El Salvador, and its Threat to Civil Society and Human Rights Defenders (2025) |

| International Center for Not-for-Profit Law Online Library | El Salvador |

NEWS

El Salvador scraps term limits (August 2025)

El Salvador’s congress has approved constitutional reforms to abolish presidential term limits, allowing President Nayib Bukele to run an unlimited number of times. The reform, reviewed under an expedited procedure, will also extend term times to from five to six years, while the next election will be brought forward to 2027.

President Bukele’s foreign agents law is fueling democratic concerns (May 2025)

Human rights organizations, politicians and experts have sharply criticized a law approved by El Salvador’s Congress as a censorship tool designed to silence and criminalize dissent in the Central American nation by targeting NGOs that have long been critical of President Nayib Bukele. The law proposed by Bukele was passed by a Congress under firm control of his New Ideas party, and bypassed normal legislative procedures. Bukele first tried to introduce a similar law in 2021, but after strong international backlash it was never brought for a vote by the full Congress.

Human rights commission calls on El Salvador to end state of emergency (September 2024)

El Salvador should end a long-running state of emergency and reinstate suspended constitutional rights after achieving significant security gains due to its anti-gang crackdown, a prominent human rights commission said. The Washington-based Organization of American States’ human rights commission said in a report it had seen the government’s data on the improved crime rate and it no longer justified the suspension of rights. President Nayib Bukele declared the initial month-long state of emergency following a wave of murders over a single weekend in March 2022.

Statement in Solidarity with Human Rights Defenders in El Salvador (May 2024)

At a joint press conference on April 18, the Movement of Victims of the Regime (MOVIR), the Committee of Families of Political Prisoners in El Salvador (COFAPPES), Humanitarian Legal Aid (Socorro Jurídico Humanitario), the “Herbert Anaya Sanabria” Human Rights Collective, and the Committee of Relatives of Victims of the State of Exception of the Bajo Lempa detailed an alarming pattern of surveillance and police interference into their participation in street marches, protests, and rallies, as well as online harassment.

As free press withers in El Salvador, pro-government social media influencers grow (August 2023)

Rights groups, civil society and even some officials criticized El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele for violating human rights in his crackdown on criminal gangs, and said that his unconstitutional bid for re-election would corrode the country’s democracy…. There is now an expanding network of social media personalities acting as a megaphone for the millennial leader. At the same time Bukele has cracked down on the press, his government has embraced those influencers.

El Salvador Extends the ‘State of Exception’ for the Ninth Time (December 2022)

El Salvador’s Congress approved another 30-day “state of exception”, which involves the suspension of various constitutional rights. The Ombudsman for the Defense of Human Rights, Raquel Caballero, stated that she had met with Security Minister Gustavo Villatoro, who acknowledged that 59,600 people have been detained since the state of exception began. As a result, on September 27, three humanitarian organizations denounced the State of El Salvador before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for the arbitrary detention of at least 152 people during the emergency regime.

ARCHIVED NEWS

10,000 police to seal off a town and search for gang members (December 2022)

El Salvador Extends State of Emergency to Curb Gang Violence (April 2022)

Nayib Bukele’s Recipe for Limiting Human Rights (July 2021)

El Salvador Defends Firing Attorney General, Top Judges (May 2021)

Bukele May Tighten Grip in Elections (February 2021)

Salvadorean President Hostile towards Independent Media (October 2020)

Sending aid is key to solving the Central American migrant crisis (November 2018)

Supreme Electoral Tribunal Announces 2019 Presidential Elections (October 2018)

Salvadoreans March Against Water Privatization (June 2018)

Investigate private agents released pepper spray on students (June 2018) (Spanish)

First Transparency Monitoring Report of the Electoral Process (January 2018) (Spanish)

Pension Law Amendments with broad citizen participation (October 2017) (Spanish)

New changes to the Electoral Code (May 2016) (Spanish)

Extraordinary Security Measures Approved (April 2016) (Spanish)

Government and civil society launch Alliance for Open Government (January 2016) (Spanish)

New contributions in the process of electoral reforms (November 2015) (Spanish)

Assembly approves law on electronic signatures (October 2015) (Spanish)

Una ley contra los delitos informáticos que respete la libertad de expresión (September 2015) (Spanish)

CSO director victim of threats (May 2015)

Organization promotes more transparency (May 2015)

Private media called to recognize international standards of freedom of expression (November 2014)

President receives Draft Law of Citizen Participation in Public Management (September 2014)

Former guerrilla wins El Salvador vote (April 2014)

U.S./El Salvador: A common ground for partnership (June 2013)

El Salvador one of only ten states to have ratified the Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (January 2013)

Dr. Tillemann travels to Peru and El Salvador (October 2012)

CSOs petition to halt REDD program (August 2012)

Civil society speaks out on constitutional crisis (July 2012)

Trade unionists denounce persecution in El Salvador (June 2012)

Progress can prevail in El Salvador (May 2012)

Legislative blunders and expectations in El Salvador (May 2012)

HISTORICAL NOTES

The origins of civil society in El Salvador can be traced to the 1960s, when early initiatives focused primarily on humanitarian aid. The sector grew significantly in the late 1980s and early 1990s, during the civil war and subsequent post-war reconstruction. Many CSOs at that time provided emergency support to marginalized populations while others emerged to address broader social welfare issues. The 1992 Peace Accords created further opportunities for expansion, both in the number of organizations and in the scope of their work.

Over subsequent decades, CSOs established mechanisms for international cooperation and financing and began to organize collectively through unions, alliances, networks, federations, and partnerships. These structures allowed them to engage in the public sphere more effectively, including by formulating policy proposals, legislative initiatives, and agreements with state agencies.

The election of a government led by Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in 2009 created new channels for citizen participation. However, CSOs were unable to coalesce around a unified national development agenda. Institutional weaknesses persisted, particularly in the government body responsible for overseeing CSOs, which has long been criticized for bureaucratic inefficiency.

During the administration of President Salvador Sánchez Cerén (2014–2019), the Five-Year Development Plan envisaged the creation of a new legal framework for CSOs. In 2019, the government presented a Not-for-Profit Social Organizations Act, which aimed to modernize procedures, streamline services, and address gaps in the existing legislation.

Following the 2021 legislative elections, the Nuevas Ideas party led by President Nayib Bukele gained a supermajority in the Legislative Assembly. This enabled the government to remove and replace officials, including the attorney general and magistrates of the Supreme Court of Justice, and consolidate control over state institutions. Within this context, the government signaled its intention to introduce measures that could restrict civic space and the activities of human rights organizations, rather than moving forward with the Not-for-Profit Social Organizations Act.